Beyond Diesel: What It Really Takes to Reduce Fuel Dependence in Remote Operations

By Paula McGarrigle, President & CEO, Solas Energy

For decades, diesel has underpinned power generation in remote and industrial operations. Mines, ports, isolated facilities, and northern communities have relied on it not because it is elegant or efficient, but because it is dependable. It can be shipped in, stored on site, and dispatched when needed. In places far from the grid, that certainty has always mattered.

But certainty comes at a cost.

Fuel logistics are complex. Prices are volatile. Storage and handling bring environmental risk. And increasingly, diesel dependence is under scrutiny from investors, regulators, communities, and operators themselves. Not because diesel has suddenly failed, but because its limitations are now impossible to ignore.

The question facing many remote operators today is no longer whether diesel works. It is whether it needs to work quite so hard.

This article reflects on early work undertaken to reduce diesel reliance in extreme and remote environments, and on the lessons from that work that continue to hold true. While technologies have advanced, the fundamentals have not changed. Diesel reduction remains, at its core, a systems challenge.

Diesel Reduction Is a Systems Question, Not a Technology Decision

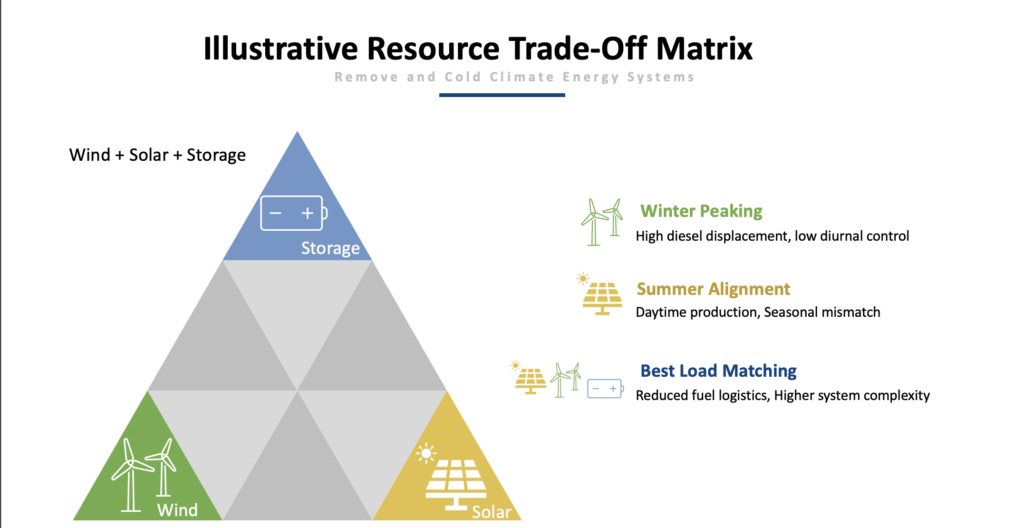

One of the most persistent misunderstandings about diesel reduction is the idea that it begins with technology choice. Wind or solar? Batteries or hydrogen? One turbine or five? In practice, those questions come later.

The real starting point is understanding how the energy system behaves as a whole: hour by hour, season by season, and under conditions that are less than ideal. Remote operations are not forgiving environments. Loads are often continuous and large. Power quality matters. Downtime is costly. And weather, terrain, and access constraints shape every engineering decision.

Reducing diesel use is not about removing generators. It is about integrating additional sources of energy in a way that strengthens, rather than undermines, the system.

That requires discipline, not enthusiasm.

Cold and Remote Does Not Mean Poor Renewable Potential

There is a long-held assumption that cold, northern, or remote locations are inherently unsuitable for renewable energy. Experience suggests otherwise.

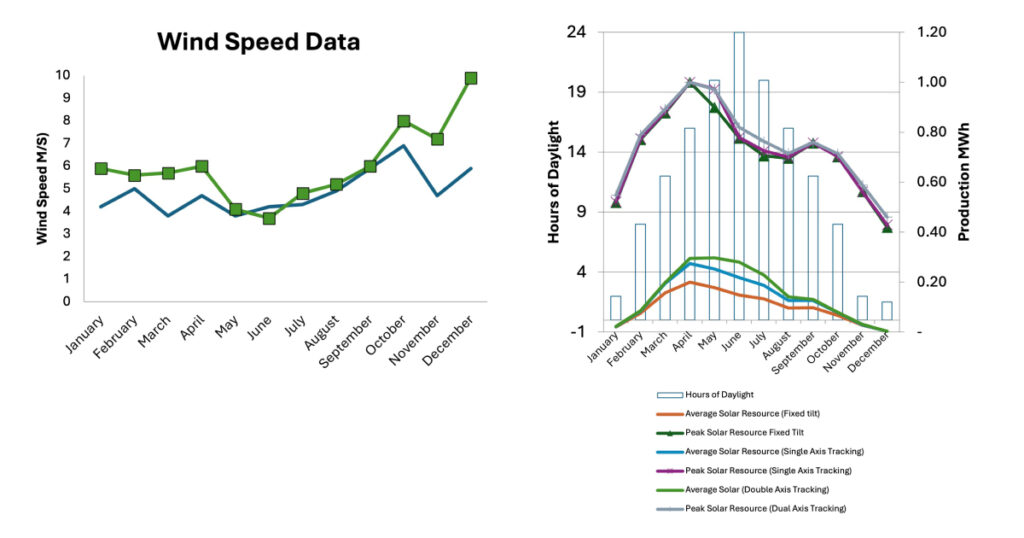

Many high-latitude environments benefit from strong and persistent wind regimes. In several cases, wind production peaks in winter, precisely when energy demand and diesel consumption are highest. Snow cover can enhance bifacial solar technology output during shoulder seasons. And when systems are properly designed, renewables can complement diesel rather than compete with it.

The challenge is rarely the availability of resource. It is the interaction between generation, load, and control.

In early diesel-reduction studies for remote industrial sites, the most important questions were not about annual energy yield, but about operational behaviour:

- How does the system respond to sudden changes in wind output?

- What happens during prolonged cold snaps?

- How low can diesel loading safely go?

- When does curtailment become necessary?

These are engineering questions, grounded in operations.

Wind–Diesel Hybrids: A Practical and Proven Path

For many remote industrial sites, wind–diesel hybrid systems remain the most practical entry point for reducing fuel consumption.

Wind offers several advantages in harsh environments:

- strong winter production profiles,

- relatively high energy yield per installed megawatt,

- compatibility with existing diesel infrastructure,

- and a long track record when appropriately specified.

But adding wind is not simply a matter of erecting turbines.

Successful integration depends on a range of considerations, including:

- renewable penetration limits, both instantaneous and average;

- generator ramping behaviour and minimum loading constraints;

- system controls capable of managing variability;

- strategies for curtailment or dump loads; and

- cold-climate turbine specifications, including anti-icing and cold-start capability.

In many early projects, the most effective outcomes did not come from maximizing renewable penetration. They came from achieving a level of diesel displacement that was meaningful, reliable, and operationally acceptable.

Seasonal Alignment Matters More Than Annual Averages

Annual capacity factors are a familiar metric, but they can be misleading in remote applications.

What matters far more is alignment: between when energy is produced and when it is needed. In several remote studies, wind generation was shown to peak during winter months, aligning closely with periods of highest diesel use. That alignment allowed for significant fuel displacement without overbuilding capacity.

By contrast, some locations exhibited strong renewable resources that were poorly matched to load profiles, limiting their practical value unless paired with storage or load management.

The lesson is straightforward: it is not just how much energy is produced, but when it is produced, that determines its usefulness.

Storage Has a Role, but It Is Not a Cure-All

Energy storage is often presented as the missing piece in diesel reduction strategies. It is one tool among many. The best energy storage will have a round-trip efficiency of 85%, so that means you are losing 15% of all energy that you are charging the energy storage with.

In remote systems, storage can:

- smooth short-term variability,

- support frequency and voltage control,

- reduce generator cycling, and

- increase renewable penetration within defined limits.

But storage also introduces cost, complexity, and maintenance considerations, particularly in cold climates. Performance at low temperatures, replacement cycles, and operational expertise all need to be considered carefully.

In several early hybrid systems, storage was deployed in a targeted way, supporting control and stability rather than providing bulk energy. In some cases, simpler solutions—such as thermal loads or controlled curtailment—proved more robust.

Storage is most effective when it is sized to the system.

In Remote Locations, Proven Technology Matters

Remote industrial sites are not test beds. When access is limited and response times are long, reliability matters more than novelty. Experience has shown that proven technologies, with established supply chains and operational track records, consistently outperform experimental solutions in these environments.

This applies across the system: turbines, controls, storage, balance-of-plant, and communications. Innovation still has a role, but it must be matched with maturity and serviceability.

In remote settings, the cost of failure is simply too high.

Diesel Reduction Is Also About Logistics and Risk

One of the less visible, but most significant, benefits of reducing diesel consumption is the reduction in logistical exposure.

In remote locations, diesel is not just a fuel. It is a supply chain involving transport, storage, handling, and environmental risk. Each delivery carries cost and uncertainty. Each litre stored brings potential liability.

Even modest reductions in diesel use can result in fewer deliveries, lower spill risk, and improved operational resilience. For some operators, these benefits alone justify serious consideration of hybrid systems, quite apart from emissions or sustainability objectives.

Why These Lessons Matter Today

The principles of diesel reduction have not changed. What has changed is the context.

Today’s operators face greater price volatility, more sophisticated stakeholder expectations, and a wider range of mature technologies. Modelling tools are better. Control systems are more capable. And the business case for resilience is clearer.

What was once considered experimental is now repeatable.

Early work in extreme environments demonstrated that diesel reduction does not mean abandoning diesel. It means using it more intelligently, as part of a balanced and resilient system.

From Pilot Projects to Long-Term Strategy

Perhaps the most important shift is conceptual. Diesel reduction is no longer a pilot exercise or a box-ticking exercise. It is increasingly part of long-term energy planning for remote and industrial operations.

The question has moved on from “Can this work?” to “What is appropriate for this site, this load, and this operating reality?” Answering that question requires experience, judgement, and a clear understanding of system behaviour. It requires respect for operational constraints as well as environmental objectives.

In extreme environments, resilience is not an abstract concept. It is designed, engineered, and tested—often in difficult conditions.

Diesel will continue to play a role in remote power systems for the foreseeable future. But its role is changing. And with the right approach, it no longer needs to carry the entire burden alone.